Want to Generate Impact? Get Creative.

Emerald Publishing's Martyn Lawrence, when offering a matrix by which research impact could be measured, wrote this: Invisible research is, by definition, low impact. He might have gone on to write that invisible research is also a waste of time and money, because what is the point of spending months researching and writing up findings only for them to gather digital dust in an online archive?

For researchers, this matters more than one thinks because funders are increasingly looking for a real return on their research dollars, euros and pounds. For example, the Ford Foundation, the second largest in the US, expects grantees to “achieve the greatest possible impact”; EU Horizon 2020 Proof of Concept grant applicants must outline the economic and/or societal impact expected from the project; and the UK’s REF, in assessing applications, gives a 25 percent weighting to the ‘reach and significance’ of impact. But what is impact and how can you generate it?

I was once told a story by Carlos Rossel when he was the World Bank’s Publisher. It was about one of their reports on AIDS in Africa. The Bank wanted to use the report to draw attention to what was then a growing problem and to raise money to help address it. Someone at the Bank had the idea of presenting the report to Bill Gates who promptly pledged $5 billion from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to fight AIDS in Africa. One copy of one report put into the hands of someone who was convinced to take action: that’s impact.

So, impact isn’t necessarily having lots of downloads or traffic to a website, impact can also be a directed process to make someone, the right someone, take action. Take, for example, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Secretary-General. When he visits ministers and presidents, he always takes a stack of publications and, one-by-one, hands over printed copies, the key findings and recommendations for change as he goes. He doesn’t just parrot what’s in the report, he adjusts the message to his audience, framing it to the local context and thereby making it more likely the minister will listen and act. The minister isn’t likely to read the report – but it is very likely she’ll hand it to an adviser and ask for a brief with recommendations. Whilst physically handing someone a copy of your work might seem an old fashioned methodology, it can be the end point in a communication strategy that had prepared the ground for the research’s message to be received and is an approach that is scalable.

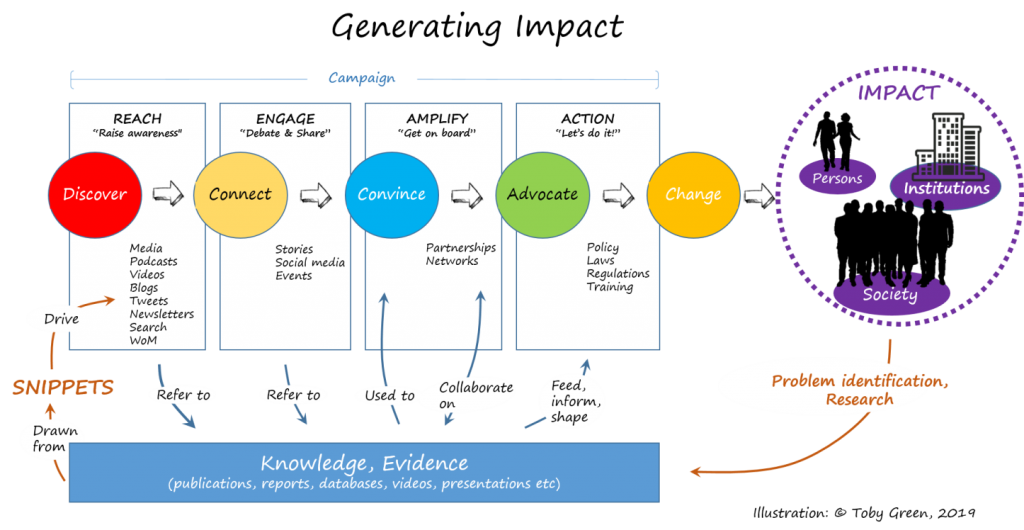

The diagram below shows the different steps from discovery to action and, importantly, the relationship between knowledge and information in this process. Persuading someone to take action, to change something, is hard and on its own the information contained in a paper is unlikely to do the job. You need to do more than just publish and hope – you need to be creative and active.

So, what can you do to make your work more impactful?

One simple thing you can do, is to be graphic. Humans are visual and are 80 percent more likely to read a text when it has an image. Gemma Sou, writing at the LSE Impact blog blog, reported that employing graphics not only helped communicate her work, it transformed her research practice, making it more relevant. Learning how to reach your audience therefore is not just an addition to your research, it can also make your research better.

After reaching an audience, authors should develop their network to build campaigns that raise awareness, stimulate debate and convince others to get on board to advocate for change. It’s important not to simply send out an email blast, or push tweets out, but to engage with your intended audience over a period of time. This means listening to what your audience is saying in their presentations, tweets and blog posts and responding using snippets from your research findings so a conversation develops.

In a recent case study, I describe how I drew attention to three of my papers published since 2017. This required a change to my normal routine in order to dedicate a little bit of time every day over a period of months to develop opportunities to engage using social media. I learned what worked and what didn’t by using two tracking and reporting tools: Kudos and Altmetric. However, getting hold of some data, especially download data, proved difficult and publishers could certainly up their game here. For me, these efforts paid off, both articles are among the journal’s most-downloaded and have Altmetric scores in the top 5 percent of all research outputs. As a result, I have received invitations to speak at conferences and write blog posts (like this one) which, in turn, develops my audience and increases my chance of making an impact.

I can hear many of you now: “but I’m too busy to promote my papers.” Let’s put this in context. If you’ve spent many months – even years – gathering data, writing up the results and getting a paper through the publishing process, isn’t it worth spending time on making sure your findings reach beyond your immediate peer group? Otherwise, aren’t you just keeping the results to yourself? A ‘launch-and-leave’ approach (do some promotion when a paper is launched and then leave the scene hoping an audience will develop by itself) is highly unlikely to generate much impact and means you’re going to get a poor return on the investment you made in writing a paper in the first place. This doesn’t necessarily mean investing time promoting each and every paper, but it does mean thinking about a strategy to communicate the results of your research so they have the best chance of making an impact.

In this digital world, funders know that there’s a data trail to every online action and are coming to expect researchers to do more than just report on citations, they want to see the evidence that your findings escaped academia’s gravitational pull and are informing a broader audience of practitioners and policy makers. Researchers who are prepared to invest as much time in promoting their works as they did writing them, and can show the results, are not only going to be more visible and impactful, they’re likely to win more grants.