If AI wrote your article, what would you lose? Some thoughts on wellbeing and writing

by Dr. Katherine Firth, author of Writing Well and Being Well for your PhD and Beyond: How to Cultivate a Strong and Sustainable Writing Practice for Life.

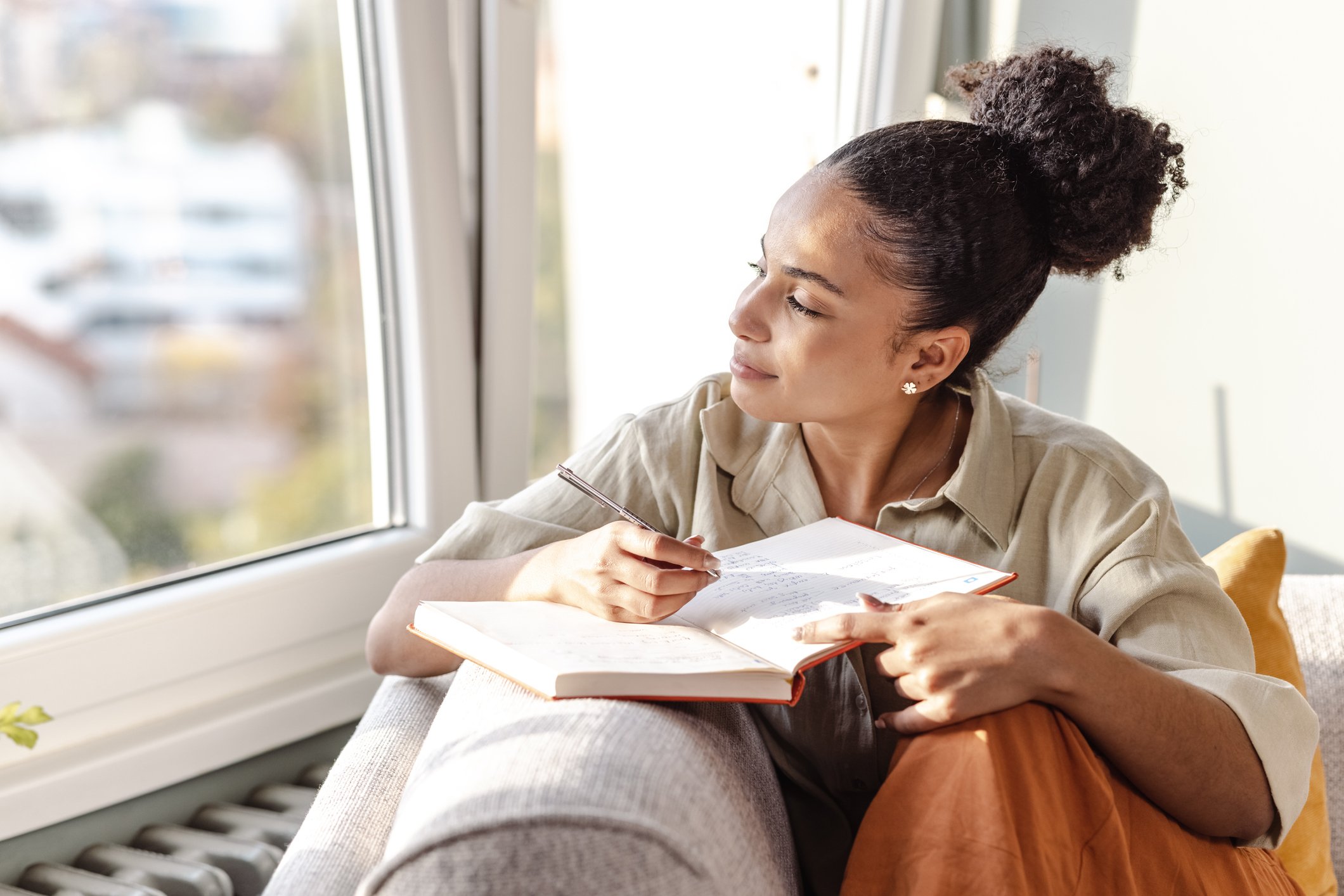

Writing is often framed as a grueling, painful and stress-inducing task, something that we can’t wait for someone else (whether a chat-bot or co-author) to do for us. But we also know that people actually like writing, that people look forward to finally have time to write as they set out on a PhD or their research leave. Writing is a chance for us to explain our cool new ideas to readers, and perhaps to change minds or make the world a better place.

I’ve recently completed a book about how writing isn’t the opposite of wellbeing, and how incorporating wellbeing into your writing doesn’t mean adding yet another thing to your to-do list, or even accepting second-rate writing. Instead, wellbeing can help us write better and feel better while writing. I include strategies that work for me personally, techniques that have worked for thousands of students around the world, or surprising tricks that writers shared with me that work for them personally.

Here are three tips that might help you make your writing work well for you.

1. Writing can often be done with other people

Researchers often identify how isolating, even lonely, academic work can be. But there’s no reason why you can’t work alongside other people at every stage of your writing project, even if you are the sole author. In my book, I point out that writing involves multiple steps, including reading and thinking, planning, putting words on paper, taking breaks from the writing, structurally editing the words, polishing up the words, and rewriting and revising. Each of these steps can be done on your own, or with other people. Set up a reading group to help you plough through that lit review material mountain. Talk to your mentor about what you might put into the next article. Join a group like Shut Up and Write where people write together. Being part of Academic Writing Month (AcWriMo 2023) is another way to write with other people, which is why it’s such an enduring part of our international writing calendar. (There’s specific advice about this in the book in sections 1.3.5 ‘Generous Reading Strategies’; 2.4.1 ‘Dialogical planning’; 3.3.3 ‘Writing with others’; 4.1 ‘A mindfulness practice for recharging: Seeing the forest for the trees’)

2. You can adapt writing to your own strengths and preferences

Your writing will have to end up looking ‘right’—with the correct spelling, font size, citation style, and academic language—if you want to pass or get published. However, because everyone has to redraft multiple times, there’s plenty of freedom in how you get started, and even how you do the bulk of the writing work. You might prefer to ‘spread’ the writing out in small blocks of work, or ‘stack’ them up in a big block. You might like to come up with the first draft using voice-to-text, or using a pen on paper. You might find that intellectually challenging material is best conceptualized through diagrams, or through a conversation with a colleague. You might even find that sometimes you find the words more easily by getting up from your desk and going for a run or a walk, or by having a quick nap. It doesn’t matter if it ’looks’ like serious writing to other people, it just matters if it progresses your writing project. You can adjust your writing place, pace, and process around your energy, time, body, brain and life—whatever that looks like. (For more specific advice on these ideas, see 1.2 ‘A physical wellbeing practice for thinking: A walking practice’; 2.3.2 ‘Writing time “spreaders” and “stackers”’; 2.3.4 ‘Breaking down a project into smaller steps’; 2.4.3 ‘Visual plans’; 3.3.2 ‘Your writing software can support your wellbeing’; 4.3.3 ‘Do you need a nap’)

3. Writing means you get to explain why your research matters

Your data isn’t self-explanatory, though it might seem that way to you. Researchers across all disciplines often just want to show what they have found and let the reader perceive the meaning for themselves: whether you have great graphs and figures; long transcripts from participants; or golden quotes from your reading. This doesn’t usually work because, in fact, you are doing original research. You have become the expert in your project and approach. No reader knows anything like as much as you do, so when they try to make an educated guess what you are telling them, they are going to guess wrong. (This is even more likely if you handed the meaning-making over to Large Language Model Artificial Intelligence). If you aren’t quite sure what your research means yet, the writing up helps you to work it out. When You do know why your research matters, what the data means, how it improves or challenges previous research, then writing is the place you get to explain that to others. (Read more about these ideas in 5.1 ‘A mindfulness practice for editing: Imagining your ideal reader’; 7. 1 ‘A mindfulness practice for rewriting: a gratitude practice for your writing’ or 7.3.4 ‘Writing towards hope: Can writing be healing?’)

So, what would you lose if you let AI take up the hard work of doing your academic writing for you? You’d lose the social connections of thinking and writing with other people, towards reaching readers and changing their minds. You’d lose the chance to include your self, your voice, your body into crafting the writing—reflecting your holistic and authentic ideas. And you’d lose the chance to explain why your ideas matter, to change the world.

If we are just churning out papers, then it doesn’t matter how they get written. But if we are expanding knowledge, and sharing that knowledge with other humans to make our world a better place or to understand our world better… then writing our own papers is a wonderful opportunity to share that knowledge with the (perhaps small, perhaps huge) group of other people who care about it as much we do.

BIO:

Dr Katherine Firth has been developing research writers for over 15 years. A co-founder of the award-winning Thesis Bootcamp program, she maintains a writing blog Research Degree Insiders https://researchinsiders.blog. She is co-author of the books How to Fix your Academic Writing Trouble (Open University Press 2018), Your PhD Survival Guide (Routledge 2020) and Level Up your Essays (New South 2021). Her new book is Writing Well and Being Well for Your PhD and Beyond, (Routledge 2023).

Look candidly at your unfinished project. Is it a stepping stone, and completion will be allow you to move ahead? Or is it an obstacle that prevents you from moving forward? Find ideas to help you determine whether to revive that piece of writing or let it go.