What Does 'Informed Consent' Mean Today?

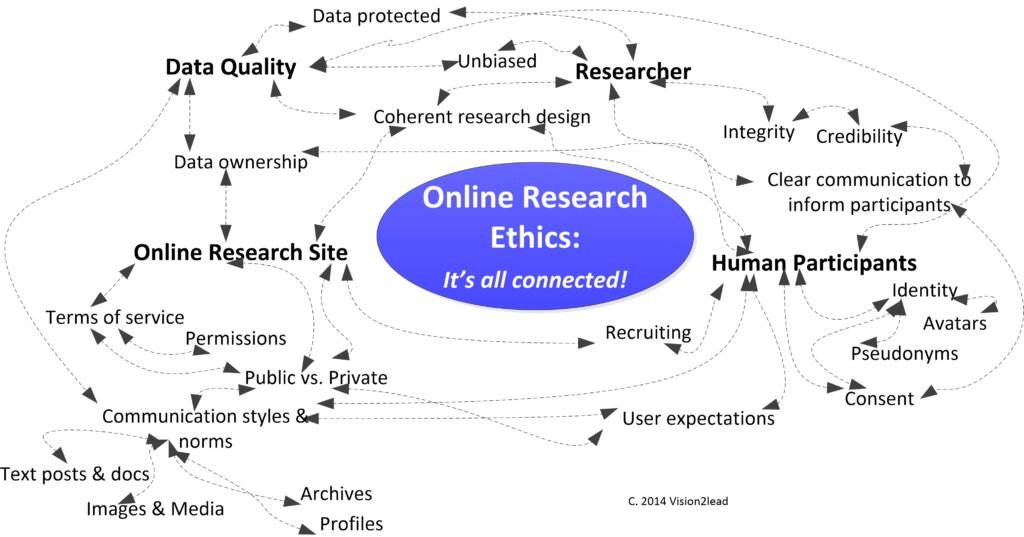

Facebook users did not consent to have their profiles and online activities acquired, sold, and used to influence activism and votes on behalf of a political campaign. This week we are being rocked by revelations that Cambridge Analytica harvested private information from the Facebook profiles of more than 50 million users without their permission. As researchers, we need to think about ethical implications for our own data collection.Here is a question to fuel your thoughts: if Facebook members had been given an End User Licensing Agreement (EULA) and/or a conventional consent agreement that allowed the Cambridge Analytica researcher to access their profiles and activities, would they  have clicked "I agree" without reading-- and gone on with their usual Facebook activities? Did those 50 million users read the Facebook terms of service and related documents before posting personal information on the site? Would those users have made a different choice, if presented with a clear, understandable explanation?I became intrigued with EULAs last year, when working on a chapter about informed consent for a book titled The Ethics of Online Research. Since my premise was that long documents that marry legalese with academese don't actually inform participants, I was interested in other ways agreements are made online. Technology companies have a few more resources than the average academic researcher (!) so I reasoned that they might have put some thought into this problem.The term informed consent is often used to describe both the process researchers use with participants to communicate expectations and parameters of the study, and the resulting record. The European Commission definition is:

have clicked "I agree" without reading-- and gone on with their usual Facebook activities? Did those 50 million users read the Facebook terms of service and related documents before posting personal information on the site? Would those users have made a different choice, if presented with a clear, understandable explanation?I became intrigued with EULAs last year, when working on a chapter about informed consent for a book titled The Ethics of Online Research. Since my premise was that long documents that marry legalese with academese don't actually inform participants, I was interested in other ways agreements are made online. Technology companies have a few more resources than the average academic researcher (!) so I reasoned that they might have put some thought into this problem.The term informed consent is often used to describe both the process researchers use with participants to communicate expectations and parameters of the study, and the resulting record. The European Commission definition is:

[I]nformed consent is meant to guarantee the voluntary participation in research and is probably the most important procedure to address privacy issues in research. Informed consent consists of three components: adequate information, voluntariness and competence.

Similar to a consent agreement, commercial enterprises use EULAs and terms of service to verify that the user is aware of the particular rules and limits for the software or platform. At the same time, they want to protect themselves from liability, legal actions, as well as from negative messages from unhappy customers distributed over social media (Salmons, 2018). Of course EULAs are necessarily different from informed consent agreements. Typically, EULA agreement must be indicated before you can use the software or platform. "I agree" is the only acceptable answer; if you don't agree, then you can't use the product. There is no negotiation with the EULA. Again, if Facebook users were presented with such a limited-option agreement, would they have clicked yes without even reading it, even with the risk to their personal information?With an informed consent agreement, we can answer questions, explain anything that concerns a potential participant, and make changes if needed. Still, we have same challenge as EULAs: can we be assured that a potential participant reads the agreement to the extent needed to truly have and comprehend "adequate information" about the study?Both commercial enterprises and academic researchers who collect data online are trying various options for communicating information in ways that will invite users to pause long enough to grasp key points.  Approaches include the use of graphics or short video clips with step-by-step explanations, interactive games, or quizzes (Salmons, 2016). I have successfully used a SurveyMonkey questionnaire, followed by a discussion about participation in the study, before beginning an interview. This example is meant to encompass a wide range of questions researchers can adapt to their own needs.Academics working with Institutional Review Boards or Ethics Committees are often constrained by required use standardized agreements-- which get longer and denser with each new possible risk. This type of consent documentation is completed before the researcher starts to collect data, but do not offer a way to check-in or address changes that emerge during the study. Unlike commercial enterprises, academic researchers need to consider ethics and agreements throughout the study and dissemination of findings. We must keep communication channels open at all stages.To improve our process and build public credibility need to work with institutional entities and research supervisors to modernize consent agreement approaches. It is more important than ever to ensure that research participants have the information they need, presented in a way that they can competently grasp. As researchers who believe in the importance of disciplined inquiry, we need to take responsibility for our part. We must take the necessary steps to merit participants' confidence that we will protect private information and use what we learn from them to generate new knowledge for the social good.Use the comment box to offer your ideas, recommendations, and/or examples of innovative and effective practices. Register on the Methodspace site to receive future posts in this series, and other posts and resources about research methods.Learn More! If you have access to the SAGE Research Methods database, find related books, chapters, cases, and videos in this Ethics and E-Research Reading List. Also see this special collection of related articles from Business & Society: The Governance of Digital Technology, Big Data, and the Internet: New Roles and Responsibilities for Business. Salmons, J. (2018). Getting to yes: Informed consent in qualitative social media research. In K. Woodfield (Ed.), Ethics in Internet mediated research. Bingley: Emerald.Salmons, J. (2016). Doing qualitative research online. London: SAGE Publications.

Approaches include the use of graphics or short video clips with step-by-step explanations, interactive games, or quizzes (Salmons, 2016). I have successfully used a SurveyMonkey questionnaire, followed by a discussion about participation in the study, before beginning an interview. This example is meant to encompass a wide range of questions researchers can adapt to their own needs.Academics working with Institutional Review Boards or Ethics Committees are often constrained by required use standardized agreements-- which get longer and denser with each new possible risk. This type of consent documentation is completed before the researcher starts to collect data, but do not offer a way to check-in or address changes that emerge during the study. Unlike commercial enterprises, academic researchers need to consider ethics and agreements throughout the study and dissemination of findings. We must keep communication channels open at all stages.To improve our process and build public credibility need to work with institutional entities and research supervisors to modernize consent agreement approaches. It is more important than ever to ensure that research participants have the information they need, presented in a way that they can competently grasp. As researchers who believe in the importance of disciplined inquiry, we need to take responsibility for our part. We must take the necessary steps to merit participants' confidence that we will protect private information and use what we learn from them to generate new knowledge for the social good.Use the comment box to offer your ideas, recommendations, and/or examples of innovative and effective practices. Register on the Methodspace site to receive future posts in this series, and other posts and resources about research methods.Learn More! If you have access to the SAGE Research Methods database, find related books, chapters, cases, and videos in this Ethics and E-Research Reading List. Also see this special collection of related articles from Business & Society: The Governance of Digital Technology, Big Data, and the Internet: New Roles and Responsibilities for Business. Salmons, J. (2018). Getting to yes: Informed consent in qualitative social media research. In K. Woodfield (Ed.), Ethics in Internet mediated research. Bingley: Emerald.Salmons, J. (2016). Doing qualitative research online. London: SAGE Publications.