Focusing: The Muse and the Mundane

By Janet Salmons, PhD Research Community Manager for Methodspace

Dr. Salmons’ most recent book from SAGE Publishing is a new edition of Doing Qualitative Research Online. If ordering from SAGE, use MSPACEQ423 for a 20% discount through December 2023.

I love writing at this desk with a view of the Rocky Mountains.

Integration of research and writing differentiates academic work from other types of writing. We analyze, critique, and build on others’ published research; we report on our own findings. Some might think that given this empirical, scientific basis for our writing, we don’t need a muse. I readily confess that I do! I don’t know how else to explain the fact that sometimes the writing just flows, but sadly, at other times it does not. I may have a perfectly clear block of time and a quiet office, but I can’t quite craft words into an interesting, insightful piece of writing. You may call this a lack of focus, and say I need to use my left brain to set writing goals, and force my typing fingers to meet them. I just don’t think it works that way, at least not entirely.

When my muse is present, I see how to meld seemingly unrelated fragments into a meaningful whole. Oddly, my muse seems to visit when I am taking a walk, or a shower. Sometimes I fall asleep while wrestling with questions and wake up with a clear sense of what I want to write. Other times, I read and re-read what I’ve written so far, go back to the articles I am referencing, but still can’t put the pieces together. Lynn Nygard, author of Writing for Scholars, suggests that

[W]riting is a two-part process: the creative part, we would put our ideas into words, so they make sense to us; and the critical part, when we try to make those words make sense to someone else. In the creative part, we let the ideas flow, make new connections, see implications and draw conclusions…. In the critical part of the process, we emerge from our own little universe and shift our perspective to that of the reader. This is where we fill in the blanks, connect the dots, and generally put into words everything the reader needs to draw the same conclusion we draw, or to see the same connection we see. (Nygard, 2015, p. 25)

Taking a walk is not a waste of time. It is a pause to refresh!

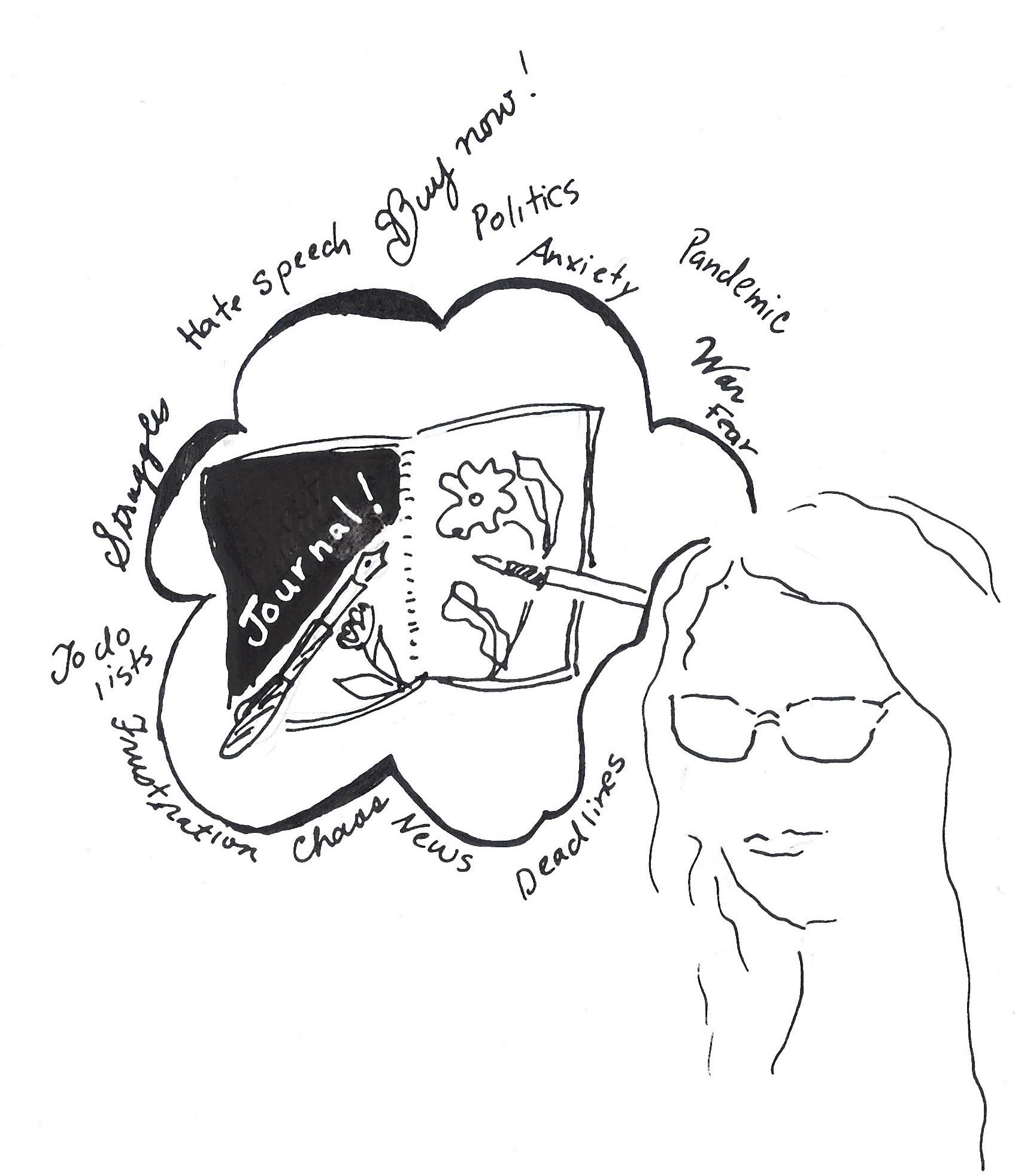

We need the presence of our muse for the creative part of writing. Alas, muses can be uncooperative-- they don’t operate on schedules or care about our due dates. They may or may not respond to our pleas or dire invitations to please return. Here are some approaches I use when my muse is off having fun somewhere else.First, instead of sitting in front of a blank page, watching the stuck word count and feeling more and more anxious about my inability to complete the project at hand, I step away from the computer.I might go for a walk, or engage in some other creative activity that does not involve words. I recently started a watercolor class, and I like to make jewelry. These activities might seem unrelated to academic writing, but I find they help me to tap into other sources of inspiration.

Another option is to vary the actual ways that I write. I step away from the academically formatted page on the screen, go back to my notebook and sketch out my thoughts. Pen in hand, I can shape major concepts and look for new ways to connect or present them. Or, I might literally sketch a diagram or a mind map that helps me to see relationships in different ways. I often develop these sketches into figures that are included them in my publications, because I think readers also find the visual presentation more readily accessible than the written narrative.

In the last couple of years, I’ve discovered that voice-to-text software has greatly improved. I find that being about to speak can unlock the creative door. I can tell it, explain it, and then go back and carry out the critical part of the process to proofread and edit. Given the need to use citations and references, I’ve created a hybrid system of speaking and typing.

Talking about the ideas, brainstorming, even arguing with others can also help us see the missing pieces. Some have the luxury of being able to readily meet for coffee (or something stronger) with peers engaged in similar struggles. For those of us no longer in school, and for those like me who work remotely, finding and nurturing a writing circle is a valuable step. Finally, if the creative muse is ignoring me, I look for other tasks I can do without her. I might clean up formatting, conduct library research, or read some new articles. I might through the critical stage on other parts of the writing project, because the review process on the previous section or chapter can trigger new thinking about what comes next. By understanding that I need the muse and the mundane, by knowing that the creative and critical parts of the process are equally essential, I avoid the anxiety that comes with the fear of the blank page. What do you do to be productive when your muse is missing?

Nygard, L. P. (2015). Writing for scholars: A practical guide to making sense and being heard (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications.

How and why should you argue in academic writing? Learn more from Dr. Alastair Bonnett, author of How to Argue.